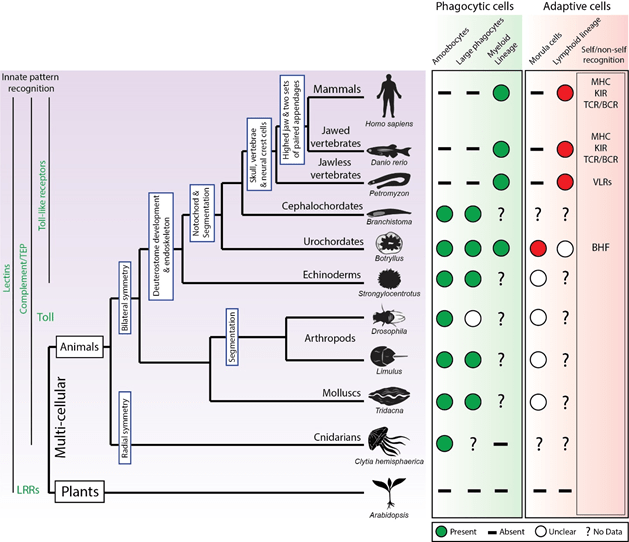

As the multicellular organism evolves and increases in size and intercellular heterogeneity, the detection and elimination of cheater cells becomes more difficult to control. Two types of cheater cells can be distinguished at this point; cells derived from the host through clonal development and foreign cells that associate with the host. Indeed, tumor cells are classified as the first type, cheating via abnormal clonal expansion and somatic mutation, whereas bacteria are classified as the latter type via infection. In both instances, the cheater cell uses the cooperative intercellular nature of the multicellular organism, often to the detriment of the host. One simple but effective feature that evolved is the development of selective barriers (like the wide variety of epithelia including skin and gut) that allow access of nutrients, while excluding harmful cells. However, these barriers can be breached by bacteria and tumor cells arise beyond the barrier. To distinguish tumor cells, bacteria or infected cells, multicellular organisms evolved several stages of recognition and a plethora of tailored responses to ensure integrity of the organism. The recognition of harmful cheater cells (pathogen, from the Greek pathos “suffering” and genes “producer of”) is carried out by the innate and adaptive immune system. The innate immune system is strategically placed at barriers where a breach may occur (for example, a bacteria entering a cut in the skin). The recognition of pathogens by the innate immune system is conserved and innately defined, driven by selective pressures from pathogens2. For example, innate phagocytic immune cells like macrophages express receptors like toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), which specifically recognizes lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a major component of the cell wall of many bacteria. A wide variety of similar innate receptors are able to recognize different but fixed pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), hence their name as pattern recognition receptors (PRRs). One of the oldest classes of PRR are lectin receptors recognizing specific carbohydrate structures on pathogens, which are even found in plants3 (Figure 1). Following pathogen recognition, innate immune cells apply phagocytosis (engulfment of target cells) as a means to deal with pathogens that are recognized. Additionally, soluble pattern recognition molecules from the complement system, like Complement factor 3 (C3), covering certain pathogens (opsonization), aid in phagocytosis and could even be traced back as far as unicellular organisms4. In contrast to fixed pattern recognition, the adaptive immune system relies on recognition through a vast diversity of randomly generated antigen-receptors expressed by T- and B lymphocytes (T- and B cells). T- and B cell receptors (TCRs and BCRs) are generated through genetic recombination by recombination-activating genes 1 and 2 (RAG1/2) in dedicated lymphoid organs. The invasion of the RAG1 and 2 genes into the Ig superfamily (Igsf) gene of the variable (V) type is now thought to be one of the primary evolutionary events that gave birth to the adaptive immune system5–7.

Figure 1 | Evolution of the cellular immune system Information regarding the cellular immune systems of invertebrate and vertebrate species. The (simplified) evolutionary tree of multi-cellular organisms with emphasis on structural and immunological divergence. Cellular components of the immune system include phagocytic cells, including amoebocytes, professional phagocytes and development of the extensive myeloid lineage. Cytotoxic morula cells have been identified in Botryllus and possibly exist in other invertebrate species, but have not been identified in vertebrates. The lymphocyte lineage has been identified in vertebrates, although undifferentiated lymphoid cells may exist in Botryllus. “Self/non-self” recognition identified in each species are shown in the right-hand column. Abbreviations: major histocompatibility complex (MHC), killer inhibitory receptors (KIRs) and T cell receptors (TCRs), leucine-rich repeats receptors of the variable lymphocyte receptors (VLRs). Adapted from Rosenthal et al.8, Flajnik5,9 and Hirano10.

The gain of randomized recognition is the defense against an almost unlimited amount of pathogens, while the cost of randomization is the potential for recognition of self-antigens, leading to auto-immunity. Nonetheless, nature has found a solution for this cost of randomization by excluding combinations that react to self-structures in a process called clonal deletion. T- and B cells that react too strongly to “self” during development are not allowed to mature and are effectively deleted. The presentation of “self” by the host cells is carried out by the highly polymorphic major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules, which seem to have evolved in parallel, but are less clearly organized compared to the variable gene regions that give rise to the TCRs and BCRs11. MHC class I (MHCI) complexes are expressed by all nucleated cells and present small pieces (peptides) of degraded cytosolic proteins on the outside of the cell membrane, a quality control check within the multicellular organism. MHC class II complexes, expressed by a class of immune cells termed antigen presenting cells (APCs), present peptides of degraded proteins from outside of the cell12. The highly polymorphic nature of the MHC alleles provides organisms with a unique fingerprint that is “taught” in the thymus and bone marrow to the variable TCR- and BCR repertoire, respectively, allowing recognition of anything “non-self”. In summary, whereas the innate immune system developed over time to recognize pathogen-specific structures in a race for reproduction, the adaptive immune response initially exploded as a result of gene duplication, genetic recombination and modes of “self” and “non-self” antigen presentation. Both have since co-evolved to the point where innate and adaptive immunity cooperate intimately in the fight against cheater cells. How these responses are coordinated depends on the type of cheater cell and the outcome is specifically tailored.

How? Read it here!

2. Buchmann, K. Evolution of innate immunity: Clues from invertebrates via fish to mammals. Front. Immunol. 5, 1–8 (2014).

3. Wang, C. et al. Extracellular pyridine nucleotides trigger plant systemic immunity through a lectin receptor kinase/BAK1 complex. Nat. Commun. 10, 4810 (2019).

4. Elvington, M., Liszewski, M. K. & Atkinson, J. P. Evolution of the complement system: from defense of the single cell to guardian of the intravascular space. Immunol. Rev. 274, 9–15 (2016).

5. Flajnik, M. F. & Du Pasquier, L. Evolution of innate and adaptive immunity: Can we draw a line? Trends Immunol. 25, 640–644 (2004).

6. Bernstein, R. M., Schluter, S. F., Bernstein, H. & Marchalonis, J. J. Primordial Emergence of the Recombination Activating Gene 1 (RAG1): Sequence of the Complete Shark Gene Indicates Homology to Microbial Integrases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93, 9454–9459 (1996).

7. Agrawal, A., Eastman, Q. M. & Schatz, D. G. Transposition mediated by RAG1 and RAG2 and its implications for the evolution of the immune system. Nature 394, 744–751 (1998).

8. Rosental, B. et al. Complex mammalian-like haematopoietic system found in a colonial chordate. Nature 564, 425–429 (2018).

9. Flajnik, M. F. & Kasahara, M. Origin and evolution of the adaptive immune system: Genetic events and selective pressures. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 47–59 (2010).

10. Hirano, M., Das, S., Guo, P. & Cooper, M. D. Chapter 4 – The Evolution of Adaptive Immunity in Vertebrates. in (ed. Alt, F. W. B. T.-A. in I.) 109, 125–157 (Academic Press, 2011).

11. Kaufman, J. Unfinished Business: Evolution of the MHC and the Adaptive Immune System of Jawed Vertebrates. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 36, 383–409 (2018). 12. Blum, J. S., Wearsch, P. A. & Cresswell, P. Pathways of Antigen Processing. Annu. Rev. Immunol31, (2013).