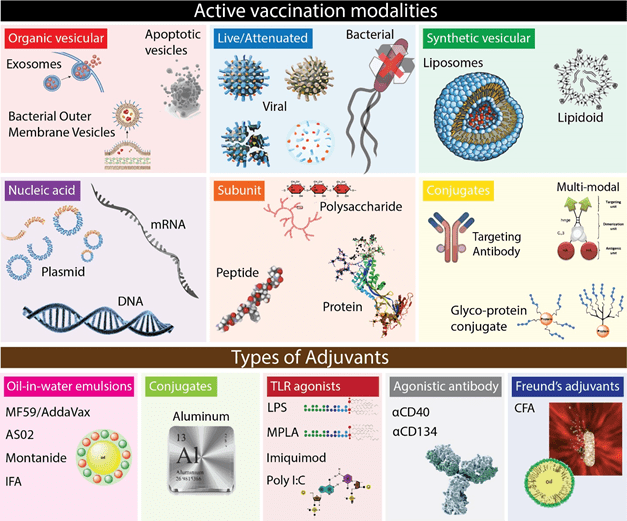

Vaccines aim to use the immune system to generate adaptive immunity in the absence of actual infection/cancer. In principle, vaccines contain antigen and innate immune activators to satisfy the preconditions (ie. 3 signals) for adaptive immunity. The delivery of antigens can be highly defined (for example, synthetic peptides) or included by association (for example, live/attenuated pathogens). Also, not all antigen modalities used in vaccination elicit innate immune activation needed for signal 2 and 3 (Figure 5). Instead, these antigens are mixed with or conjugated to immunogenic compounds (adjuvants) capable of activating dendritic cells. The prerequisites for using any of these compounds is largely defined by 1) the characteristics of the pathology for which one vaccinates and 2) prior knowledge on immunogenic antigens presented in the case of infection/malignancy. For example, using live/attenuated viral strains allows immunity to the virus without knowledge on the immunogenicity or type of immune response needed for protection. In contrast, using peptide or DNA vaccines that contain defined antigen sequences requires prior knowledge on the antigen to which immunity is required.

Figure 5 | The form factor of vaccines; antigen carriers and innate stimulators. Several antigen formulations exist aimed at providing specificity to T- and B cells.

A recent example of a pathogen to which a wide variety of vaccines is being developed is Zika virus, which can cause severe nerve damage (Guillain-Barré syndrome) and microcephaly in children from infected carriers96. Zika virus has a single-stranded RNA genome that is translated into a single polyprotein that is then proteolytically cleaves into individual proteins. First, antibodies directed against the Zika envelope (E) protein provided varying levels of protection when passively transferred to the infected host97–99. However, passive transfer of neutralizing antibodies does not confer long term protection, which requires active adaptive immune responses. A formalin-inactivated whole Zika virus vaccine has shown protective cellular and humoral immunity in mice100. Next, a plasmid DNA vaccine containing segments coding for the Zika premembrane (prM) and E proteins induced protective antibodies in mice and nonhuman primates100–102. Virus-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were also detected100. Both the DNA and inactivated Zika vaccines have since entered clinical trials103. While antibody responses in these studies are evidently enough to provide a level of protection, the cellular response aids at several levels. It has recently been shown that CD4+ T cells are required to the generation of a humoral response to Zika virus in mice104. Also, conserved Zika virus-derived CD8+ epitopes have been demonstrated in humanized mice, with the majority of the CD8+ T cell responses directed to the E protein105,106. Peptide vaccination with these epitopes provided protection to Zika-induced encephalitis and reduced Zika virus levels in humanized mice105. Additionally, peptide vaccination also reduced Zika infection in the placenta and protected offspring during pregnancy107. Indeed, vaccines aimed at cellular responses to Zika virus infection have now also entered clinical trials108. To further boost the immunogenicity of inactivated Zika vaccines, aluminum hydroxide (alum) is used as adjuvants in clinical trials103,109. Alum is now used for a century and boosts dendritic cell recruitment and activation110–112. In summary, successful Zika vaccines include 1) innate immune stimulators, 2) T cell epitopes and 3) antigens for antibody production.

A second recent example of successful vaccine design is the therapeutic immunization against solid tumors like melanoma. Originally thought to be completely incapable of preventing cancer, the last decade has proven the potency of anti-cancer immunity. Cancer immunotherapy practically started in the late 19th century when a young bone surgeon named William B. Coley, who injected his cancer patients with heat-killed Streptococcus pyogenes and Serratia marcecsens. Coley previously found 47 case reports in which concomitant infection caused the remission of normally lethal forms of cancer and anecdotes that cancers were cured in patients that survived the infections caused by major surgeries like amputation113. He reasoned the systemic inflammatory state of the patient killed cancers and that artificial infections using a heat-killed vaccine would do the same114–116. Coley ended up achieving an unusual high percentage of durable clinical responses to soft tissue sarcomas, lymphomas and testicular carcinomas using “Coley’s toxins”113. Regardless of his successes and some exposure (Figure 6), a lack of understanding in his immunotherapeutic approach and the eventual rise in surgery and radiotherapy prevented any widespread use of Coley’s treatment protocol117.

Figure 6 | New York Times report 1908

A similar approach using attenuated bacteria was effectively used 80 years later, successfully treating non-muscle invasive bladder cancer using the tuberculosis vaccine Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) in 1976118. It is still standard treatment to this day. Not long after, IL-2 was identified and isolated, which showed its capacity to induce T cell proliferation. Pioneering work from Steven Rosenberg is the late 80s showed the clinical usefulness of IL-2 treatment in metastatic cancer119,120. In 1991, it was shown that cytotoxic T cells could actively recognize tumor antigen121, although they do not seem particularly successful in patients with growing tumors. Tumors provide unique challenges in the generation of vaccines that induce anti-tumor responses. Tumors are derived from the host’s own cells, are inherently immune suppressive (see 10.1.1 Introduction – Tumor immune suppression) and show heterogeneity among patients. The nature of tumor cells requires the immune system to completely eradicate the tumor cell lineage by cytotoxicity. Indeed, cytotoxic CD8+ T cells are excellent mediators of anti-tumor immunity122,123. Therefore, most active cancer vaccines are aimed at inducing cytotoxic CD8+ T cell responses, although effector CD4+ T cells have been shown to be crucial for at least some forms of anti-tumor immunity35,124–127. Similarly to attenuated virus vaccines, allogeneic tumor cells have been attenuated, modified and used in early clinical trials128–130, most notably GVAX131. GVAX, irradiated tumor cells genetically engineered to produce GM-CSF, has shown some clinical efficacy with little side effects132–134. Tumor cell derived vesicles like exosomes have also been proposed to be adequate antigenic sources for cancer vaccines135. However, with the discovery of mutated immunogenic tumor antigens, called neo-antigens, research has shifted to antigen identification and patient-tailored vaccines. The prevalence of somatic mutations in among human cancers has been shown to drive immunogenicity (and therefore evolutionary suppression or immune escape) due to the presence/presentation of mutated “non-self” neoantigens to CD8+ T cells136–140. Identification of these neoantigens by novel genomic and bioinformatics approaches allows the identification of patient-specific antigens, which can be used for personalized vaccine design127,141–144. Once identified, neoantigen vaccines can be used as peptides142,143,145,146, peptide conjugates147,148, mRNA144,149 and peptide-pulsed DCs150. Indeed, neoantigen-defined vaccination strategies are slowly becoming the standard approach in cancer therapeutics. These two examples provide context of the requirements for protective immunity and how vaccination strategies may capitalize on these features.

That was it on introducing vaccine design!

96. Miner, J. J. & Diamond, M. S. Zika Virus Pathogenesis and Tissue Tropism. Cell Host Microbe 21, 134–142 (2017).

97. Sapparapu, G. et al. Neutralizing human antibodies prevent Zika virus replication and fetal disease in mice. Nature 540, 443 (2016).

98. Abbink, P. et al. Protective efficacy of multiple vaccine platforms against Zika virus challenge in rhesus monkeys. Science (80-. ). 353, 1129–1132 (2016).

99. Dai, L. et al. Structures of the Zika Virus Envelope Protein and Its Complex with a Flavivirus Broadly Protective Antibody. Cell Host Microbe 19, 696–704 (2016).

100. Larocca, R. A. et al. Vaccine protection against Zika virus from Brazil. Nature 536, 474 (2016).

101. Dowd, K. A. et al. Rapid development of a DNA vaccine for Zika virus. Science (80-. ). 354, 237–240 (2016).

102. Zhao, H. et al. Structural Basis of Zika Virus-Specific Antibody Protection. Cell 166, 1016–1027 (2016).

103. Barrett, A. D. T. Current status of Zika vaccine development: Zika vaccines advance into clinical evaluation. npj Vaccines 3, 24 (2018).

104. Elong Ngono, A. et al. CD4+ T cells promote humoral immunity and viral control during Zika virus infection. PLOS Pathog. 15, e1007474 (2019).

105. Wen, J. et al. Identification of Zika virus epitopes reveals immunodominant and protective roles for dengue virus cross-reactive CD8+ T cells. Nat. Microbiol. 2, 17036 (2017).

106. Elong Ngono, A. et al. Mapping and Role of the CD8+ T Cell Response During Primary Zika Virus Infection in Mice. Cell Host Microbe 21, 35–46 (2017).

107. Regla-Nava, J. A. et al. Cross-reactive Dengue virus-specific CD8+ T cells protect against Zika virus during pregnancy. Nat. Commun. 9, 3042 (2018).

108. Poland, G. A. et al. Development of vaccines against Zika virus. Lancet Infect. Dis. 18, e211–e219 (2018).

109. Lin, H.-H., Yip, B.-S., Huang, L.-M. & Wu, S.-C. Zika virus structural biology and progress in vaccine development. Biotechnol. Adv. 36, 47–53 (2018).

110. Kool, M. et al. Alum adjuvant boosts adaptive immunity by inducing uric acid and activating inflammatory dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 205, 869–882 (2008).

111. Lambrecht, B. N., Kool, M., Willart, M. A. M. & Hammad, H. Mechanism of action of clinically approved adjuvants. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 21, 23–29 (2009).

112. Eisenbarth, S. C., Colegio, O. R., O’Connor, W., Sutterwala, F. S. & Flavell, R. A. Crucial role for the Nalp3 inflammasome in the immunostimulatory properties of aluminium adjuvants. Nature 453, 1122–1126 (2008).

113. Decker, W. K. & Safdar, A. Bioimmunoadjuvants for the treatment of neoplastic and infectious disease: Coley’s legacy revisited. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 20, 271–281 (2009).

114. Coley, W. Contribution to the knowledge of sarcoma. Ann. Surg. 14, (1891).

115. Coley, W. The treatment of malignant tumors by repeated inoculations of erysipelas: with a report of ten original cases. Am J Med Sci 105, 487–511 (1893).

116. Coley, W. Treatment of inoperable malignant tumors with toxins of erysipelas and the bacillus prodigiosus. Trans Am Surg Assn 12, 183–212 (1894).

117. Hoption Cann, S. A., van Netten, J. P. & van Netten, C. Dr William Coley and tumour regression: a place in history or in the future. Postgrad. Med. J. 79, 672 LP – 680 (2003).

118. A., M., D., E. & A.W., B. Intracavitary Bacillus Calmette-guerin in the Treatment of Superficial Bladder Tumors. J. Urol. 116, 180–182 (1976).

119. Rosenberg, S. A. et al. Observations on the Systemic Administration of Autologous Lymphokine-Activated Killer Cells and Recombinant Interleukin-2 to Patients with Metastatic Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 313, 1485–1492 (1985).

120. Rosenberg, S. A. et al. A Progress Report on the Treatment of 157 Patients with Advanced Cancer Using Lymphokine-Activated Killer Cells and Interleukin-2 or High-Dose Interleukin-2 Alone. N. Engl. J. Med. 316, 889–897 (1987).

121. van der Bruggen, P. et al. A gene encoding an antigen recognized by cytolytic T lymphocytes on a human melanoma. Science (80-. ). 254, 1643 LP – 1647 (1991).

122. Hadrup, S., Donia, M. & thor Straten, P. Effector CD4 and CD8 T Cells and Their Role in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancer Microenviron. 6, 123–133 (2013).

123. Farhood, B., Najafi, M. & Mortezaee, K. CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes in cancer immunotherapy: A review. J. Cell. Physiol. 234, 8509–8521 (2019).

124. Spitzer, M. H. et al. Systemic Immunity Is Required for Effective Cancer Immunotherapy. Cell 168, 487-502.e15 (2017).

125. Martin-Orozco, N. et al. T Helper 17 Cells Promote Cytotoxic T Cell Activation in Tumor Immunity. Immunity 31, 787–798 (2009).

126. Bos, R. & Sherman, L. A. CD4<sup>+</sup> T-Cell Help in the Tumor Milieu Is Required for Recruitment and Cytolytic Function of CD8<sup>+</sup> T Lymphocytes. Cancer Res. 70, 8368 LP – 8377 (2010).

127. Tran, E. et al. Cancer Immunotherapy Based on Mutation-Specific CD4+ T Cells in a Patient with Epithelial Cancer. Science (80-. ). 344, 641 LP – 645 (2014).

128. Nemunaitis, J. et al. Phase II trial of Belagenpumatucel-L, a TGF-β2 antisense gene modified allogeneic tumor vaccine in advanced non small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients. Cancer Gene Ther. 16, 620–624 (2009).

129. Fakhrai, H. et al. Phase I clinical trial of a TGF-β antisense-modified tumor cell vaccine in patients with advanced glioma. Cancer Gene Ther. 13, 1052–1060 (2006).

130. Powell, A., Creaney, J., Broomfield, S., Van Bruggen, I. & Robinson, B. Recombinant GM-CSF plus autologous tumor cells as a vaccine for patients with mesothelioma. Lung Cancer 52, 189–197 (2006).

131. Dranoff, G. et al. Vaccination with irradiated tumor cells engineered to secrete murine granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor stimulates potent, specific, and long-lasting anti-tumor immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 90, 3539 LP – 3543 (1993).

132. Nemunaitis, J. et al. Phase 1/2 trial of autologous tumor mixed with an allogeneic GVAX® vaccine in advanced-stage non-small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Gene Ther. 13, 555–562 (2006).

133. Le, D. T. et al. Safety and Survival With GVAX Pancreas Prime and Listeria Monocytogenes–Expressing Mesothelin (CRS-207) Boost Vaccines for Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 1325–1333 (2015).

134. Lipson, E. J. et al. Safety and immunologic correlates of Melanoma GVAX, a GM-CSF secreting allogeneic melanoma cell vaccine administered in the adjuvant setting. J. Transl. Med. 13, 214 (2015).

135. Wolfers, J. et al. Tumor-derived exosomes are a source of shared tumor rejection antigens for CTL cross-priming. Nat. Med. 7, 297–303 (2001).

136. McGranahan, N. et al. Clonal neoantigens elicit T cell immunoreactivity and sensitivity to immune checkpoint blockade. Science (80-. ). 351, 1463 LP – 1469 (2016).

137. Rosenthal, R. et al. Neoantigen-directed immune escape in lung cancer evolution. Nature 567, 479–485 (2019).

138. Lee, C.-H., Yelensky, R., Jooss, K. & Chan, T. A. Update on Tumor Neoantigens and Their Utility: Why It Is Good to Be Different. Trends Immunol. 39, 536–548 (2018).

139. Alexandrov, L. B. et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 500, 415 (2013).

140. DuPage, M., Mazumdar, C., Schmidt, L. M., Cheung, A. F. & Jacks, T. Expression of tumour-specific antigens underlies cancer immunoediting. Nature 482, 405–409 (2012).

141. Robbins, P. F. et al. Mining exomic sequencing data to identify mutated antigens recognized by adoptively transferred tumor-reactive T cells. Nat. Med. 19, 747 (2013).

142. Castle, J. C. et al. Exploiting the Mutanome for Tumor Vaccination. Cancer Res. 72, 1081 LP – 1091 (2012).

143. Yadav, M. et al. Predicting immunogenic tumour mutations by combining mass spectrometry and exome sequencing. Nature 515, 572 (2014).

144. Kreiter, S. et al. Mutant MHC class II epitopes drive therapeutic immune responses to cancer. Nature 520, 692 (2015).

145. Ott, P. A. et al. An immunogenic personal neoantigen vaccine for patients with melanoma. Nature 547, 217 (2017).

146. Keskin, D. B. et al. Neoantigen vaccine generates intratumoral T cell responses in phase Ib glioblastoma trial. Nature 565, 234–239 (2019).

147. Kuai, R., Ochyl, L. J., Bahjat, K. S., Schwendeman, A. & Moon, J. J. Designer vaccine nanodiscs for personalized cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Mater. 16, 489 (2016).

148. Li, A. W. et al. A facile approach to enhance antigen response for personalized cancer vaccination. Nat. Mater. 17, 528–534 (2018).

149. Sahin, U. et al. Personalized RNA mutanome vaccines mobilize poly-specific therapeutic immunity against cancer. Nature 547, 222 (2017).

150. Chen, F. et al. Neoantigen identification strategies enable personalized immunotherapy in refractory solid tumors. J. Clin. Invest.129, 2056–2070 (2019).